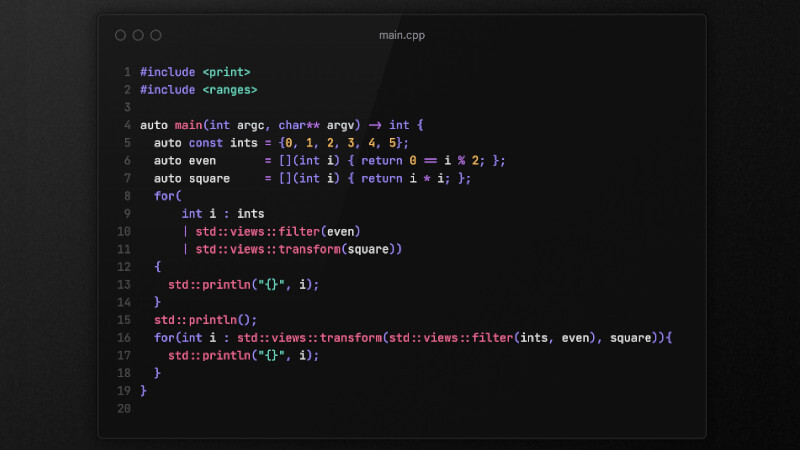

What’s the difference using it like this?

Without

new.

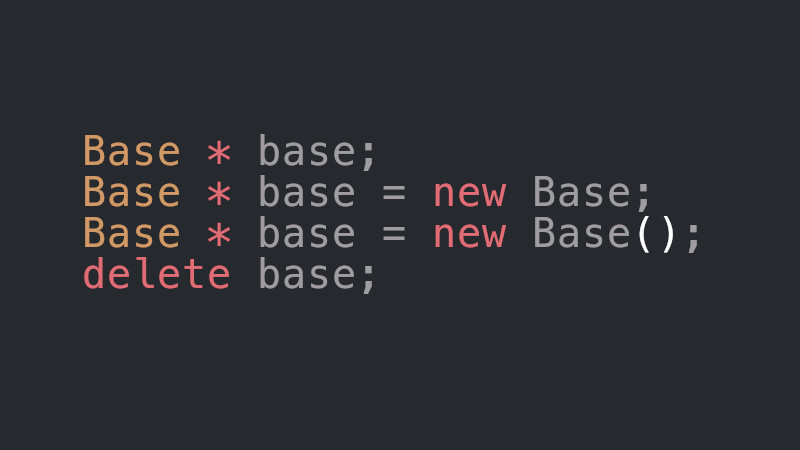

Base * base;And so?

With

new, but WITHOUT parentheses inBase.

Base * base = new Base;Or like this?

With

new, but WITH parentheses inBase.

Base * base = new Base();Initial concepts

Firstly, the difference between using new and delete and not using involves dynamic memory allocation versus automatic allocation (or static allocation if it is a global variable or member of a class).

When you use new, you are dynamically allocating memory on the heap, and when you use delete, you are freeing that memory.

In other words, the programmer is responsible for allocating and releasing memory. This allows for finer control over the object’s lifetime. This is best suited for real-time applications, where automatic allocation can significantly influence performance.

However, depending on the programmer’s skills, this can be classified as risky behavior, where it makes it easy for the programmer to forget to deallocate and generate future memory space problems.

The ideal is not to delete only in the destructor, but rather immediately after using and knowing that you will no longer use members or member functions of the allocated object.

// Bad ideia

Base * base1 = new Base();

base1->call();

Base * base2 = new Base();

base2->call();

delete base1;

delete base2;// Good idea

Base * base1 = new Base();

base1->call();

delete base1;

Base * base2 = new Base();

base2->call();

delete base2;Do not use pointers, allocate them to the Stack, example:

Base base;Difference between application modes

In C++, the use of parentheses in the expression new Base() or new Base when allocating an object dynamically has some subtleties, especially in relation to which is called value initialization and default initialization.

No parentheses

Base* base = new Base;This expression performs the default initialization of the Base object, it behaves differently depending on the context of the Base class.

If Base is a class with a user-defined constructor, the constructor is called. If Base is a class without a user-defined constructor, the class’s non-trivial members are not initialized.

With parentheses

Base* base = new Base();This expression performs the value initialization of the Base object, it also behaves differently depending on the context of the Base class.

If Base has a user-defined constructor, the constructor is called. If Base does not have a user-defined constructor, all members are initialized to their default values (0 for fundamental types, nullptr for pointers, etc.).

Examples

#include <iostream>

class Base{

public:

intx;

Base(){

std::cout << "Constructor was called!\n";

}

};

int main(){

Base * base1 = new Base; // The value of x may come out with incorrect data or nullptr

std::cout << "The value of x is: " << base1->x << '\n';

delete base1;

Base * base2 = new Base(); // The value of x will be 0 (zero)

std::cout << "The value of x is: " << base2->x << '\n';

delete base2;

}Depending on your operating system and/or version of your compiler, in both cases 0 (zero) may appear, but in other cases users who will use your software are at risk of erroneous data.

Conclusion

The ideal is to use smart pointeirs, but if you are developing a real-time application and performance is compromised, prefer to use WITH PARENTHESES: Base * base = new Base();.