Today we will continue the Go Series. In the previous episode we saw an introduction and the first steps.

In this episode we will see:

- Variables;

- Concatenation;

- Constants;

- and Data Types.

Variables

In Go there are data types, but you can create a variable without informing the type using the := operator, for example creating a variable of type string:

variable := "Hello, Golang!"

package main

import "fmt"

func main (){

variable := "Hello, Golang!"

fmt.Println(variable)

}Using the reserved word var

package main

import "fmt"

func main (){

var variable = "Hello, Golang!"

fmt.Println(variable)

}Rules for creating variables:

- Do not combine forms by mixing:

var variable := "Hello, Golang!"variable = "Hello, Golang!"variable := "Hello, Golang!" - Only name variables with numbers if the first character is a letter:

1variable := "Hello, Golang!"variable1orvar1avel - The only special character that should be used is the underscore, the order in which it appears is independent:

_variable,variable_,variable_,var1_avel,_vari_1avel`…

Use the reserved word var or the := operator for any data type, examples:

package main

import "fmt"

func main (){

var num = 10

var hello = "Hello"

world := "World"

var price = 49.54

fmt.Println(num)

fmt.Print(hello)

fmt.Print(" ")

fmt.Println(world)

fmt.Println(price)

}Variables, of course, can vary the value, but use both var and := only when creating for the first time, examples:

Correct:

var name = "Marcos Oliveira"

name = "Terminal Root"

fmt.Println(name)Output:

Terminal Root.

Wrong:

var name = "Marcos Oliveira"

var name = "Terminal Root"

fmt.Println(name)Error compiling/running:

./arquivo.go:7:7: name redeclared in this block

Another observation is that if you try to use a variable that you did not initialize (only declared, but did not assign any initial value) using the reserved word var, there will be an error when executing/compiling the program, for example:

package main

import "fmt"

func main(){

var name; // ERROR

name = "Marcos"; fmt.Println(name)

}Also note that the

;is optional in Go.

VARIABLES CREATED AND NOT USED, GENERATE ERROR IN COMPILE!

Concatenation

The operator to concatenate in Go is the + (plus), however, this only works (logically) for strings. Usage example:

package main

import "fmt"

func main (){

var hello = "Hello"

world := "World"

fmt.Print(hello + ", " + world + "!\n")

}Note that we can also use escaped characters to skip a line:

\nin

Constants

To create constants, use the reserved word const.

Unlike variables, under no circumstances can the value be changed:

package main

import "fmt"

func main(){

const pi = 3.14

fmt.Println(pi)

}If you try to redefine the constant named pi you will get an error:

package main

import "fmt"

func main(){

const pi = 3.14

pi = 6.18

fmt.Println(pi)

}

/hello.go:7:6: cannot assign to pi (declared const)

Data Types

When we use both var and := the data type is used dynamically (the default size of the type is assigned) and this can influence performance depending on the type of application/program you are creating.

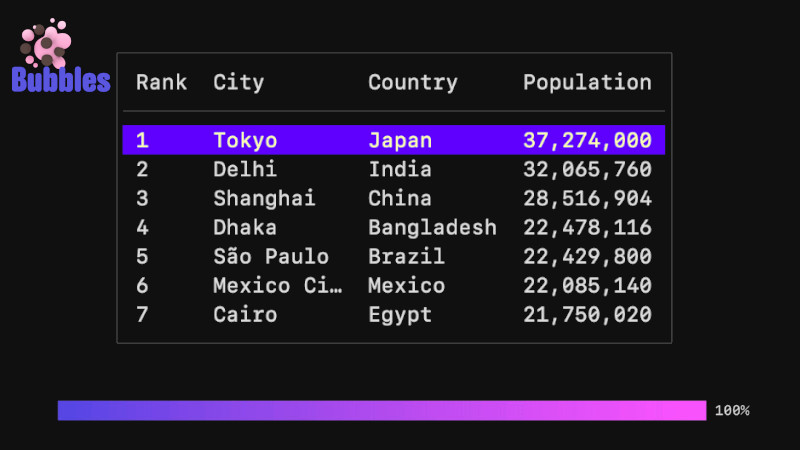

So, for each content a type is used, for example, for a variable to have the content "Hello, Golang!" Go dynamically creates the type string, for a number without punctuation it uses int, with punctuation it is float, and among others, see the basic types in the table below:

To understand some information in the table you need to have intermediate knowledge of Mathematics

| TYPE | DESCRIPTION | EXAMPLE |

|---|---|---|

byte |

for a single character | a |

string |

for a set of characters | "Hello, Golang!" |

int |

for positive and negative numbers | 10 or -10 |

float |

for irrational numbers | 9.36 |

complexN |

for complex numbers, where N must be the size | 6i |

rune |

for unicode symbols (emoji, for example) | U+0030 |

bool |

for values according to boolean mathematics | true or false |

Some of the basic types mentioned above have subcategories that can vary the size of the variable, examples:

- The

inttype has:int8,int16,int32andint64the number represents the amount of bits, for example,int64can store up to 64 bits or 8 bytes (64 / 8) and so on, the standard will depend on the operating system that is running the Go code. - The

floattype is subdivided into:float32andfloat64, the default is 64 . - The

complexNtype must be:complex64orcomplex128.The other types do not have subdivisions, but for the

booltype the default isfalse.

Creating a code defining the type:

It only works when combined with the reserved word

var

package main

import "fmt"

func main(){

var helloworld string = "Hello, Golang"

fmt.Println(helloworld)

}If you are familiar with other programming languages, notice that the type is declared after the name.

Other examples:

package main

import "fmt"

func main(){

// String

var helloworld string = "Hello, Golang"

helloworld = "Hello, Go!"

fmt.Println(helloworld) // Hello, Go!

// int

var num int = 42

fmt.Println(num)

// float32

var x float32 = 54.892

fmt.Println(x)

// complexN → complex64

var yx complex64 = 2 + 5i

fmt.Println(yx)

// byte

var letter byte = 'a'

fmt.Println(letter) // 97 according to the ASCII table

// rune

fmt.Printf("%U\n", []rune("☎")) // we will see more details later

// bool

var p bool; // or var p bool = true

fmt.Println(p) // false

}The likely outputs of the above code:

Hello, Go! 42

54,892

(2+5i)

97

[U+260E]

falseThat’s it for this episode, see you next time!